"Anyone

who attempts anything original in this world must expect a bit of

ridicule."

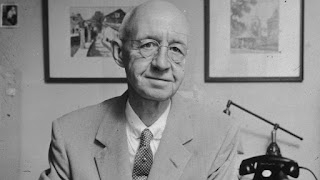

Clarence

Birdseye was obsessed with food. He would eat anything. "Scrumptious"

was how he described lynx marinated in sherry. He sampled seal meat, owl, polar

bear, filleted rattlesnake sizzled in pork fat, hawk, porcupine (de-quilled, presumably) and skunk (but mercifully

only its front half).

He

even made a string-powered gizmo to catch starlings in the yard of his

Massachusetts home. Whether the device's purpose was to rid him of pests, provide

dinner, or both is lost to history.

The editor of his college yearbook

teased him by putting this phony quote by his photo: “I ain’t afeer’d o’bugs, or toads, or worms, or snakes, or

mice, or anything.” Indeed, when he

was 10, he wondered if there might be a market for muskrat. It turned out there

was, and with the proceeds from the beasts he trapped and sold, he bought a

shotgun.

4,495 Ticks

His

college nickname was "Bugs." This turned out to be prescient. His

family's financial woes forced him to drop out. Soon he found work as a

naturalist out west. He helped researchers study Rocky Mounted Spotted Fever

and was at liberty to kill any animal that might be carrying the creepy

creatures. He shot more than 1,000 deer, elks, mules, and mountain sheep, as a

result, collected precisely 4,495 ticks. To his credit, his report did much to

advance medical and scientific knowledge about the disease.

Later

he bred foxes for their fur. This led him to Labrador where he saw something

that would change his life. He watched the

Inuit ice fishing. When they yanked fish from the ocean, the 30-degree-below zero

air made them freeze rock solid almost before they hit the ground. Then, wonder

of wonders, when the fish thawed, they tasted fresh.

Frozen

food already existed, but no one had mastered the process of chilling the edibles, getting them to market, and then keeping them below freezing in stores. Existing frozen food was so

appallingly bad not even prison inmates would eat it. Wanting to ward off

riots, New York state banned it in its penitentiaries. Stores selling frozen

food had to display signs in their windows that resembled warning labels.

Starting

around 1915 Birdseye started to experiment, first with cabbage and then with

caribou in sea water and ice. In 1922 an ice cream company gave him permission

to run experiments in its plant. The next year Birdseye started his own

company.

To

simplify production, he decided to sell his frozen foods in uniformly-sized

small rectangular boxes. Then he had to master multiple challenges. He perfected

waterproof inks. He devised glues that would withstand freezing. He conjured up

filleting machines, and he designed wrappers. (He persistence led DuPont to

invent cellophane.)

Frozen Into Tidy Blocks

The

key to his manufacturing process lay in his invention of the "multiplate

freezing machine." It compressed whatever was being frozen into tidy

blocks, thus preventing germs from entering and making the shipping easier.

As

clever as Birdseye was, no one wanted to buy his food. Railroads shunned his

wares fearing they'd make a mess. Sanitation officials, wary of

disease-carrying food, didn't like the idea. Stores had no freezers, and

shoppers were no different from prison convicts. They also loathed all things

frozen whether they were haddock or green peas.

Enter

Marjorie Merriweather Post, the grand dame of The Post Company, famed for its

many breakfast cereals. Legend has it that when her yacht sailed into

Gloucester where Birdeye had his factory, her cook served her goose for dinner.

It wasn't just any goose. He had bought one of Birdseye's frozen birds at the

market.

She

loved it, and after nagging her father for three years, she got him to buy Birdseye's

company for the then fantastic sum of $22 million. The truth is that she was

smart as a whip and, goose or no goose, saw a smart business move and made the

deal happen all by her female self.

“A Scientific Miracle”

Birdseye

went to work for Post and lived happily and wealthily ever after. Its financial

wherewithal created the infrastructure that allowed the industry to grow. Post

gave grocery stores display freezers. It taught clerks how to use them and sell

the chilly food. It sold grocers frozen food on consignment to minimize their

risk. Lavish advertising promised housewives the best of summer's luscious

fruits in winter. Stamping its good journalism seal of approval, The New York

Times raved in 1932 that frozen food was "a scientific miracle in home

management."

"Change,"

said Birdseye, "is the very essence of American life." What he

neglected to add was that to make that change happen it takes someone with the courage

to defrost old-fashioned thinking.

Buy the book "Courage 101: True Tales of Grit & Glory" at Amazon!

MORAL: In a crisis, don't freeze.

Buy the book "Courage 101: True Tales of Grit & Glory" at Amazon!

No comments:

Post a Comment