“If they don’t know how smart you are,

you’ve got an upper hand on them."

In

February 1936, a 21-year-old Joe DiMaggio played for the San Francisco Seals, a Yankees farm team. He’d been MVP the year before, hitting .398 with 34 homers.

They were thinking about bringing him to the big leagues. First they needed

to test him—to see if he was as good as all that. A phone call went out—not to

a major leaguer—but to a Negro League pitcher playing for a

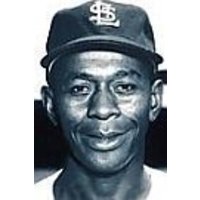

southern California team in the off-season. His name—Satchel Paige. Some say he

was the greatest pitcher in baseball history.

The

game was tied 1-1 in the tenth. Paige had 14 strike-outs. After three at bats,

DiMaggio was hitless. With two outs and a runner on third, Joltin’ Joe chopped one to Satchel’s right. He nabbed it, but his only throw

was to second. The relay came an instant too late. DiMaggio was safe. The runner scored. Game over. The telegram from the Yankees' scout to

the owners read: “DiMaggio all we hoped he’d be.”

Later,

DiMaggio would say Paige was the best pitcher he ever went up against.

Paige’s reaction?

“I got more notice for losing that game that I did winning most of my other

games.”

Paige’s 41-year career sounds like something

that could only exist in Hollywood. Just as Babe Ruth learned to play ball in

an orphanage, Paige mastered the game during five years in a reformatory.

“Those years there did something to me,” he said. “They made a man out of

me….You might say I traded five years of freedom to learn how to pitch.”

He kept an almanac

The lanky six-foot-three right

hander became the oldest major league rookie in 1948 at the age of 42. He’d

been playing ball since 1926 in the Negro Leagues on teams everywhere from Mobile,

Alabama, to Bismarck, North Dakota, often in dismal conditions and living in

third-class accommodations.

He kept an almanac of his

performance. It records that he played in 2,500 games for 250 teams and won

2,000 of those games. His records also say he had 21 wins in a row, 50

no-hitters, and 62 consecutive scoreless innings. If the numbers sound

outrageous, consider that Paige played year-round for 41 years as a

barnstormer, in the Negro Leagues, in Latin America, and in the majors.

After

six years in the integrated majors, he coached and played minor league ball. At

the age of 62 he struck out Hank Aaron when he was a minor-leaguer. Paige

played his last pro game in 1966 when Lyndon Johnson was President—42 years after

taking the field as a pro during the Coolidge administration.

How

good was he? On more than a few occasions he felt so confident of his ability

to strike out the opposition that he told fielders to come in. In other words,

he had them all sit down. The stunt didn’t always work, but it worked often

enough. His eye was so good that from the pitcher’s mound he could knock a

matchbook off the top of a stick.

Jackie Robinson won lasting fame

when he broke baseball’s color barrier in 1945. He was 13 years younger than Paige,

and Paige, long a star, would have commanded a higher salary. Perhaps more

important, Robinson’s taciturn temperament enabled him to endure slurs from

fans that Paige would have struggled with.

“Jackie

didn’t have to go through half the back doors as me, nor be insulted by trying

to get a sandwich as me, nor be run out of places as me,” Paige said years

later. “I couldn’t have took what Jackie took.”

Later,

Robinson said Paige was “the greatest Negro pitcher in the history of the game,

a compliment Paige took as a back-handed insult.

"If

they don't know how smart you are…"

Paige

was far a sour character. He was a master showman. He played hundreds of

exhibition games in which a black team would take on a white team. He had a

lazy gait that made him look unthreatening to white fans, yet when the time

came, he could turn on the heat to please black fans—and white ones, too. Paige

once told his friend Harlem Globetrotter Meadowlark Lemon “If they don’t

know how smart you are, you’ve got an upper hand on them.”

By

the late 1930s he’d become such a star that he could assemble barnstorming

teams of black players and demand the best accommodations.

In

1937, he had the moxie to tell the press he had devised a test for determining

whether black players should be in the major leagues. It had three parts:

First, the World Series winner would play a team of black all-stars, and the

blacks would not get paid unless they won. Second, he would play for any major

league team and defer his salary unless he did a good job. Third, ultimately

the fans would decide—they would vote to determine whether blacks could play.

To

whom did he give this interview? Of all places, the Communist Daily Worker

newspaper. His notions went nowhere, except at the headquarters of the FBI which started a

file on him.

Fans

didn’t care. He sold out major league stadiums in the late 1940s and early

1950s. Once after a game while sitting in a whirlpool, he was surprised to see

a funny-looking man with a big bushy moustache and eyebrows kneeling beside him

asking for an autograph. It was Groucho Marx.

Perhaps

the fast-talking comedian envied Paige’s way with words. Here is how the

pitcher once described his art on the mound: “I got bloopers, loopers, and

droopers. I got a jump ball, a be ball, a screw ball, a wobbly ball, a

whipsy-dipsy-do, a hurry-up ball, a nothin’ ball and a bat dodger. My be ball

is a be ball ‘cause it ‘be’ right there where I want it, high and inside.”

Today

Paige is best known not for his blazing fastball, longevity, or sufferance of

years playing without the recognition he deserved. He's remembered for his rules for staying

young. They are:

*

Avoid fried meats which angry up the blood.

*

Go very light on the vices, such as carrying on in society. The social ramble

ain’t restful.

*

If your stomach disputes you, lie down and pacify it with cool thoughts.

*

Avoid running at all times.

*

Keep the juices flowing by jangling around gently as you move.

*

Don’t look back. Something might be gaining on you.

Did

Paige actually live up to his maxims? Well, maybe. He loved fried foods and had

legendary stomach upsets. He trained by going on runs as long as 10 miles. Did

he look back? No one knows. But he kept going.

MORAL:

Broil that catfish.

No comments:

Post a Comment