"I am

going to get a direct hit."

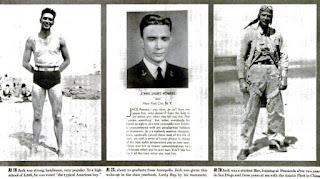

His

classmates at George Washington High School voted him “the typical American boy.” That

sums up the story of Navy Lieutenant John James Powers.

"He

never thought of himself as any sort of hero," said LIFE Magazine. But Powers

was a great hero. In the Battle of the Coral Sea in early May 1942, his

superhuman actions decisively turned the battle in the Allies favor—at the cost

of his own life. For his heroism and sacrifice, he won the Medal of Honor,

America's highest military honor.

Powers

grew up "in the

big city wilderness," according to LIFE. To be precise, he called the Washington

Heights section of Manhattan home. "He shot immies [glass marbles with swirls],

played cops and robbers, had fist

fights, joined the Boy Scouts,

went hiking, fishing, and sailing." In high school he was "a good but not an exceptional student.”

He must have been better than good,

because he won a hard-to-get appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy at

Annapolis. Cadets nicknamed him Jo-Jo. His roommate wrote his senior profile in

the yearbook. It read: "Sure we know him, who doesn’t? That “certain something” that makes everybody his

friend on sight is Jo’s most noticeable trait.

"Entirely unencumbered with any peculiarities, hobbies, or

diversions, Jo is a markedly positive character, keen, caustically cynical

about most of his life of ours, yet with a sense of humor always in charge of the most stable temperament you’ve ever seen. Never trust

him to respect conventionalities. He’s a hilarious rebel, and his own man.

You'll like him for it all the more when you meet him."

Punch

in the face

He must have been a tough guy among

tough guys—he made the boxing team. Double tough, he could take a punch in the

face and give one back.

After graduating in 1935, he did a tour in China and in

1942 was serving as a squadron commander aboard the U.S.S. Yorktown, flying a Douglas Dauntless dive bomber.

A Japanese armada planned to invade

the strategic port of Port Moresby in New Guinea. Thus far in World War II, the

Japanese had been unstoppable. Had their plan succeeded, their next target

would have been Australia. That's why Australians call the Battle of the Coral

Sea "The Battle That Saved Australia."

(The event

was historic for two other reasons. First, it was the first battle in which

aircraft carriers engaged each other. Second, it was the first naval battle

fought at a distance. Neither side saw each other or directly fired on each

other.)

The

Allies went into battle outnumbered. Besides the Yorktown, they had only one

other carrier in the fight, the U.S.S. Lexington. The Japanese had three

carriers—the Shoho, Shokaku, and Zuikaku.

During

the first day of the battle, Powers sank the carrier Shoho. He "scored a direct hit on [the] carrier which burst

into flames and sank soon after," according to his Medal of Honor

citation.

“Scratch

one flattop,” radioed Lt. Robert E. Dixon, a pilot from the U.S.S. Lexington.

That

wasn't enough to satisfy Powers. On that day and the next, according to his

citation, "in the face of blasting enemy anti-aircraft fire" he "demolished

one large enemy gunboat, put another gunboat out of commission, [and] severely

damaged an aircraft tender and a twenty thousand ton transport."

The next

morning, immediately before takeoff, Powers gave a pep talk to the men in his

squadron. "Remember—the folks back home are counting on us," he told

them. "I am going to get a direct hit if I have to lay it on the flight

deck."

That is

what he did. To make good on his promise, he led his squadron to the Shokaku. Once there, he dove his plane

from 18,000 feet through a barrage of fierce anti-aircraft fire directly onto

the carrier's deck.

Awed by his valor

Whether

Powers intended to crash onto its deck is unclear. He was last seen through

smoke and debris 200 feet above the carrier. The Douglass Dauntless was known

to be difficult to fly when laden a 500- to 1,000-pound bomb.

Though

the Shokaku stayed afloat, it

required such extensive repairs it was unavailable to the Japanese at the

Battle of Midway, the decisive battle of the Pacific war in which the Japanese

lost four carriers.

Awed by

Powers' valor, President Roosevelt devoted a Fireside Address to him in

September 1942. He repeated what Powers told his fellow fliers—"The folks

back home are counting on us."

Then FDR

drove his message home: “You and I are the folks back home," and he went on, asking his listeners, are we “playing our part ‘back home’ in winning

the war?” Then he answered his own question, saying, "We are not doing enough.”

A year

or so earlier on Father’s Day, Powers sent a telegram to his father who

had served in the Navy and fought in the Spanish-American War. The message

read: "Dear

Dad one thousand miles away

doesn’t’ make any difference and your bad son is thinking of you hoping that he

is worthy of being called a chip off the old block."

He was worthy.

MORAL:

Do what needs doing for your folks back home.

No comments:

Post a Comment